Dear Esther is nearly five years old, but it often feels older. It’s such a landmark in the world of games, so influential in its founding of a now widely recognised sub-genre, that I tend to think of it as something from the mid-2000s. When I heard there was to be a performance of the game with live musicians at the Barbican I scrambled to acquire a couple of tickets.

Dear Esther is in many ways an ideal candidate for this sort of treatment; it’s short (the event took less that 80 minutes), linear, has no fail state, and is focussed on its artistic components—the music, narrative, and environment.

That I refer to it as a performance, rather than a screening or a play-through, is quite deliberate.

Once I got over my brief internal doom-mongering (‘What would happen if the game crashed mid performance?’) I realised that I was enjoying what might be considered the fanciest of Let’s Plays. I hadn’t really considered the fact that someone was playing the game until they bumped ever so slightly into a rock a few minutes in, which made me abruptly aware that there was a style to the player’s actions, that they were making a lot of decisions about how to progress along even that relatively restricted island path.

The player dwelled in some places, admiring views, whilst they sped up in other, walking past luminescent etchings of chemical structures on cave walls with barely a glance—I wanted them to turn so that I might look at them and see if I could understand. When the narrator (the excellent Oliver Dimsdale) spoke the player stopped or slowed, softening the sound of footsteps and encouraging the audience to focus on the words and music.

I guessed the identity of the player and checked my programme to verify my suspicions when the performance was over—it was Dan Pinchbeck, of course, the game’s creative mastermind. This information brings new considerations of its own. How does a creator play their game? Is their play style the best way to play it? When I play I explore every path, even dead ends, and linger amongst the ruins, but if the creator considers the chemical etchings not worth examining then do they really matter? And can we as an audience derive a genuine sense of exploration and wonder from watching a player who is so very familiar with every gull and stone of the space? At times he seemed to be rushing along—was this a practical consideration of the performance (of course we can’t watch all night) or does this convey over-familiarity with the landscape? There’s no running commentary as there would be with a regular Let’s Play, no explicit motivation for his decisions. Why did he linger in the empty cowshed but hurry through parts of the caves?

The orchestra had a conductor but Pinchbeck was himself a performer and the true conductor, the musicians and narrator responding to his decisions and movements.

I noticed also that some of the narration seemed different to that found in my copy of the game, and that the music, rather than being almost constant as it is in-game, was reserved for particular moments in each section. I’m not sure whether these are artefacts of the Landmark Edition, my route through the game or changes made just for this event.

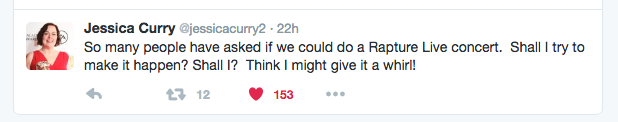

Jessica Curry, the composer, tweeted that they might one day do a similar event for Everyone’s Gone to the Rapture. Such a performance of Rapture would surely open up even more questions in these veins. I’ve mixed feelings about the use of narrative and space in Rapture (and a imminent blog entry on the topic), but have been considering whether its less linear approach and freedom of movement is actually detrimental to the narrative. If performing the game as with Dear Esther, the player on stage would have to pick one route to follow to complete the game in a timely fashion; Rapture does lay out a recommended route, but it presented as just that, recommended. Unlike Dear Esther, you can wander off if you like. If the creator performs the game live, however, and sticks to said route, does that suggest that there’s nothing terribly worthwhile to be gained from wandering and going off-piste? And what if nothing is lost by sticking to the main route? Can the freedom still be beneficial in the game? Does it serve any purpose?

Anyway, I’ve gone off-piste myself, possibly to the detriment of this narrative. Perhaps I should just accept that the performance of Dear Esther was curated, directed, conducted in a particular way this particular time, and that it might be different if performed again. But if working in the arts sector has taught me anything, it’s that how you choose to present things matters; it’s a comment on the work and, if it’s your work, that comment is authoritative.

Regardless of all the above, I very much enjoyed seeing Dear Esther live. I certainly didn’t expect it to be quite so thought-provoking. The musicians and narrator were excellent and the music wonderful. I’d love to see more game performances. Of course, if they do perform Rapture live I’ll be there in a heartbeat.

As a footnote, the lovely Rosa Carbo-Mascarell has created a fascinating map of the island Dear Esther is set on, littered with secret references. I hear it sold out at the Barbican, but keep an eye out for copies online.