Whilst driving up the motorway last Saturday I received a call from a friend.

“I’ve got two tickets to see Neil Gaiman talking with Philip Pullman about fairy tales on Monday, but can’t go. Do you want them?”

After shouting “Yes!” repeatedly at the hands-free kit, I found myself sat in the audience at the Cambridge Theatre on Monday evening. It was clear that the event was a sell-out – the place was rammed. The theatre normally hosts the excellent musical ‘Matlida’, and I loved the brightly-coloured jumble of letters that formed the stage surround.

The event was introduced by host Rosie Boycott, who announced that Philip Pullman was sadly unable to join us that evening. Apparently he had taken a fall earlier in the day and wasn’t well enough to attend. This was quite disappointing (and I hope he recovers quickly), but in his stead we were introduced to our Philip Pullman ‘impersonator’ for the evening, children’s author Meg Rosoff. In addition, Audrey Niffenegger (of The Time Traveler’s Wife fame) was also hauled out of the audience to do a reading of The Three Snake Leaves from Pullman’s Grimm Tales (a retelling of the classic tales).

Despite Mr Pullman’s absence, the conversation was both interesting and entertaining. It threw up some aspects of fairy tales that I hadn’t considered before, but that I felt were worth sharing. Let me list them in an exciting, bullet-point style for you:

Fairy tale justice makes no exceptions.

The female character in The Three Snake Leaves betrays her husband. In short, she tries to murder him and run off with another man after the ‘hero’ essentially sacrifices himself for her earlier in the story. She is a princess, and when her father learns of her treachery he has both her and the accomplice killed.

The justice of fairy tales is fairly absolute; you do a bad thing, you get caught, you get punished – regardless of who your father is. This is partially to do with the fact that…

There is no characterisation in fairy tales, just a series of wants. It’s all plot.

By and large, these characters don’t even have names. They are types, devices to facilitate the story. In The Three Snake Leaves the man wants to marry the princess, so he works to achieve that. The princess later wants to be with the sailor, so she works to achieve that.

These characters don’t exist beyond their actions in the narrative. We could take the plot of a fairy tale and apply it to more realised characters – add a little depth and psychological turmoil to their actions – but then the story would be character-driven, not plot driven. Which brings us to…

Heroes in fairy tales just happen to be heroes by virtue of being the main character; they don’t want the world to be a better place.

This statement was made with reference to the superheroes we see in comics and films today. Most superheroes want to improve the world in some way, to fight some great evil, to prove something. The main characters in fairy tales simply try to get what they want – wants that are rarely altruistic and often material. They are not struggling to achieve a great goal like the brave or virtuous heroes of Homer, nor like the principled heroines of Austen; and they’re certainly not trying to save the world.

Fairy tales don’t really have a moral backbone, just important lessons. i.e. If you don’t listen to good advice and instead go into the woods, you’ll be burnt alive. People lie, and people will take advantage of you, etc.

So what’s the point of these stories, of these ‘heroes’? If they’re not telling us to be ‘good people’, then do they teach us anything at all?

Yes indeed. These are life lessons, with a liberal dash of entertainment. As I said before; if you’re bad and you get caught, you’ll be punished. If you think you know better than everyone else, you’re probably going to be proved wrong (in a painful fashion). These stories tell us not to cheat on our significant others, not to go into the woods at night, to think things through before we leap to conclusions. They’re practical.

There are no ‘original’ versions of fairy tales, and we’re now adding the subtext back into them.

The Grimm fairy tales exist in a number of versions, some different to others. In an earlier rendition of Rapunzel, the witch only realised that Rapunzel was receiving a guest when the girl became noticeably pregnant – not very Disney. These stories weren’t initially aimed at children, but that’s who liked them most so the stories were toned down and lost some of their more adult themes. That said, the speakers argued that there weren’t really any original versions of the stories, just different editions.

In any case, Meg observed that much of the subtext that was once stripped out of the tales is now being added back in with their resurgence in popular media (see below). These days we seem to like a touch of darkness in our stories.

Devolution of gods in stories: Religious tales > Myths > Fairy tales > Legends.*

Neil shared a theory of his about stories and magic. He argued that, looking back through history, stories go from being about the gods, to featuring gods, to having a lot of magic, to having little magic. The gods fade from stories with time. He told us that the same folk tales exist in both Europe and America, but in America the magical elements are normally missing. He said that this theory is at least in part what inspired perhaps his most renowned novel, American Gods.

Fairy tales are making a comeback.

It’s obvious that fairy tales are gaining popularity again. They’re on our televisions in things like the fun Once Upon a Time, and in our comics in things like Fables. They’re not quite how the brothers Grimm envisioned them, of course, but the stories remain recognisable. I love seeing these modern takes on traditional archetypes and narratives, how they’re twisted into something new that fits today’s society. It serves to show how enduring and flexible the tales are, how some stories can weather the passing centuries and societies and still be interesting.

Neil rounded off the evening by reading his great short story Click Clack the Rattlebag, which (at the time of writing) is still available to download for free from Audible. It’s a lovely spooky story that was put out for Halloween, and is well worth a listen.

All in all it was a great evening, and it really gave me some things to think about, particularly with regards to my own writing. My thanks to all the speakers and the absent Mr Pullman.

As an aside, I was interested to learn that Neil writes his novels longhand with a fountain pen. Well, two alternating fountain pens, to be accurate; each with a different colour of ink in it so he can see how much he’s written each day. I like to write longhand with my fountain pen, but I hadn’t considered using different inks to mark progress. I might give it a go.

*I’m definitely going to explore this idea more thoroughly at some point in the future.

—

Bonus Scene:

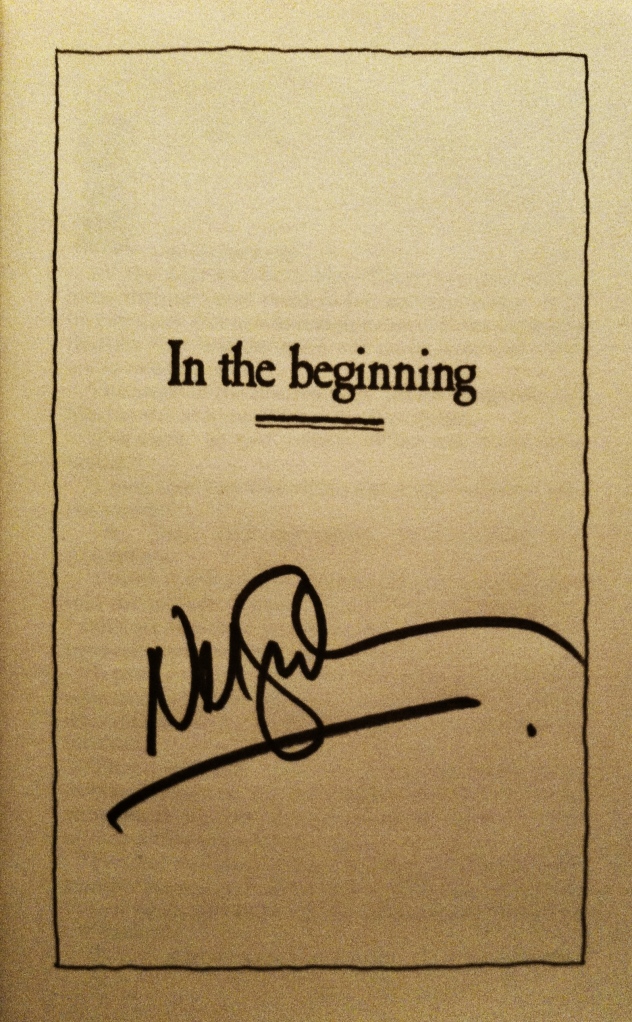

My friend and I lined up for some time to have our books signed by Neil Gaiman, who very kindly stayed to sign the books of hundreds of people, whilst also being very friendly.

I don’t normally collect signatures, and there is only one book that I care to have signed by its authors.